JS Example

let createCounter = function(n) {

let theCounter = n;

return function() {

theCounter++;

return theCounter;

};

};

const counter1 = createCounter(10)

console.log(counter1());

//prints 11

console.log(counter1());

//prints 12

const counter2 = createCounter(20)

console.log(counter2());

//prints 21ES6 Version

function createCounter(start = 0) {

let count = start;

return () => {

count++;

return count;

};

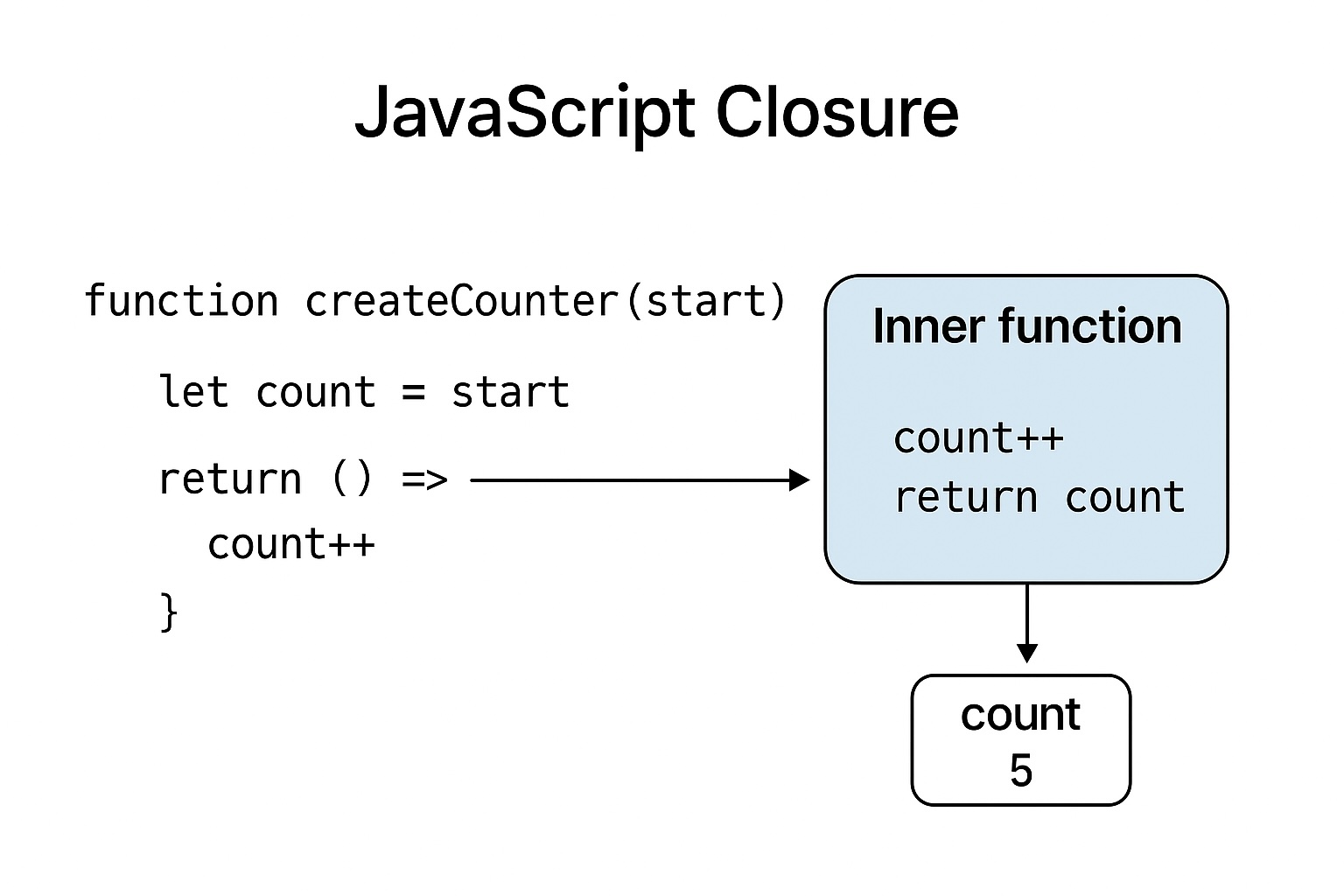

}Each call to createCounter(...) produces a small function that remembers the value theCounter. Calling the returned function increases that remembered value and returns it.

counter1 and counter2 each keep their own remembered theCounter.

It is sometimes helpful to think of a closure as a function plus a little backpack of variables it can see from where it was created (its lexical environment).

createCounterreturns the inner function. That inner function still has a reference to the environment wheretheCounterequals10. We store the returned function incounter1.

The invocation of createCounter has finished, but the environment is not removed because the returned function still points to it. The function carries the environment with it.

Why can this be so confusing?

- Invisible state — functions usually look like: input → output. Closures add hidden memory: the function now also depends on variables it “remembers”. That hidden state makes behavior less obvious at a glance.

- Life after returning — normally local variables disappear when a function returns. With closures the locals persist because a returned inner function keeps them alive. That violates many people’s first mental model of “locals get cleared”.

- Shared vs separate environments — sometimes people expect every function to get a brand new copy of variables; other times a variable is shared between many functions. That nuance causes bugs (especially in loops).

- Mutation and unexpected memory retention — closures can keep large objects in memory unexpectedly (memory leak risk) or can be mutated from multiple places.

The pattern below makes the API clearer (since you can see the methods that operate on the hidden state).

function createCounter(n) {

let theCounter = n;

return {

increment() { theCounter++; return theCounter; },

get() { return theCounter; }

};

}

const c = createCounter(5);

console.log(c.get()); // 5

console.log(c.increment()); // 6FINALLY! (the loop / var problem)

A famous confusing example:

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

}, 10);

}

// likely prints: 3 3 3for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

}, 10);

}

// prints: 0 1 2Why? var i is function-scoped, so each loop iteration uses the same i. The timeout callbacks all share that single i, and by the time they run, i is 3.

let creates a fresh binding for each iteration, so each closure captures a distinct i.

Quick diversion on what function-scoped means:

- If

varappears inside a loop → the whole function owns that variable

(not just the loop block) - If

varappears inside anif→ the whole function owns it

(not just theifblock) - If there is no surrounding function → it becomes a global variable

This is different from let and const, which are block-scoped (they belong to the nearest { ... } block).

And why is this an example of a closure?

Each function() passed to setTimeout closes over the variable i.

Meaning:

- The callback function remembers the variable

ifrom its surrounding scope (the loop’s outer function or the global scope). - That variable is not copied — it is referenced.

- All the callbacks refer to the same

i, becausevarcreates a single binding for the entire function, not one per loop iteration.

This is directly what a closure is:

A function that “remembers” and retains access to variables from its outer scope even after that scope has finished executing.

Short recap

- The original code works because each call to

createCounter(n)creates a distinct environment containingtheCounter, and the returned function closes over (remembers) that variable. - Closures are powerful (private state, factories, callbacks) but confusing because they introduce hidden, persistent state and subtle sharing rules.

Leave a Reply